Unfortunately, this burgeoning resort was officially segregated in 1900. People of color were not welcome on the Atlantic City beaches or Boardwalk except as workers behind the scenes, entertainers, or handlers of the rolling boardwalk chairs. For a few years in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Black tourists were allowed on the beach and Boardwalk only one day of the year, just after Labor Day, when the customary tourist season had ended. An article in The Atlantic City Press, September 6, 1906, records that the operators of the theaters and other amusements welcomed people of color for that one-day outing. During the Jim Crow era, Black tourists were directed to the unofficial Black beach along Missouri Avenue on the north side of town. This segregated arrangement did not change until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Postcards from Atlantic City's early days not only revealed the existence of racial discrimination and segregation, but they also employed it to appeal to white visitors in ways that were often less than subtle. The card below, published by Hugh C. Leighton Company of Portland, Maine, depicts several horseback riders on a postcard mailed in 1908. The image reveals three Black riders on white horses and three white riders on dark horses, and the printed description reads, “Three chocolate drops on whites; three whites on chocolate drops.” The man on the right seems to be in charge and gives the impression that the tableau was carefully arranged as an attempt at humor.

"Black on white, White on black," Postcard humor, Atlantic City, circa 1908.

Detail of back of Black/White riders postcard.

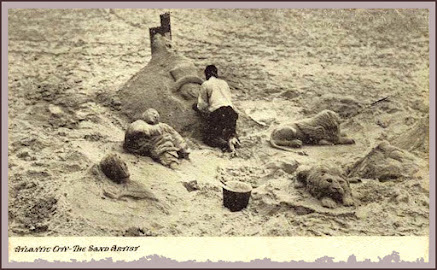

Historical records, however, identify at least one early twentieth-century sand artist as African-American, Owen Golden. Mr. Golden was well accepted by both spectators and his fellow artists. Although he was reported to have only one arm, he produced quality work that pleased his audience.

One-armed, sculptor circa 1910. Possibly Owen Golden, an African American.

Postcard published in 1907 by Hubin’s Big Post Card Store,

welcoming the conventions of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.

(Fellow in derby hat is sculptor James Taylor.)

As the number of sand artists increased, some boardwalk businesses began to complain that they were losing customers, and the city struggled with rowdy crowds, pickpockets, objections to subject matter that included nudes, and the growing number of less-skilled artists who produced poor-quality work. Eventually, the city responded by regulating the sand artists with licenses, quality standards, and design approval.

The sand-sculpture art form struggled into the 1930s despite increased competition from other attractions like “Human Roulette” and “Human Niagara” carnival rides, pageants, theater performances, and concerts. The final blow (pun intended) came in 1944 when the Great Atlantic hurricane struck Atlantic City, ravaging the Boardwalk, flooding many hotels, and destroying the amusement piers along the beach. The sand sculptures and the stands the artists had built were also lost. The city leaders, finally seeing an excuse to rid themselves of what had become an increasing nuisance, removed the remaining sculpture structures.

Competitive sand sculpture had planted its feet firmly in the sand under the Atlantic City boardwalk and spread from there to beaches around the world, but after the hurricane, competitive sculpture was finished in Atlantic City for the next half-century.

Sand sculpture as an art form with occasional competitions continued to be part of beach cultures with a strong revival of the art in California in the 1970s and other contests scattered on the world's beaches. In Texas, Walter McDonald and Lucinda Wierenga started Sandcastle Days in 1988 on South Padre Island, and the annual event continues today.(3) In 1997, the first annual SandFest(4) was organized in Port Aransas, Texas. That same year, one hundred years after Philip McCord first sculpted “Cast Up By the Sea,” BeachFest ’97 took place in Atlantic City, with a sponsored “Sandtennial” sculpting contest of more than twenty sculptors working with tons of sand for the crowd.

In 2013, John Gowdy, a New Jersey-based “international” sand artist, and others arranged for the World Championship of Sand Sculpture to return to Atlantic City! With the help of AC Alliance, The World Championship of Sand Sculpting Event began in Atlantic City on June 13, 2013.

2013 World Championship of Sand Sculpting, Atlantic City.

Okay, back to the Mystery of Philip McCord and James Taylor:

Below is a postcard mailed in 1910 with a later version of James Taylor's “Cast Up by the Sea.” Many contemporary accounts of Philip McCord’s 1897 sculpture in Atlantic City exist, and sand sculptors commonly regard McCord as the “godfather” of their art. However, we find only scant historical records of the event and no photographs of McCord.

1910 Postcard, Monterrey, California.

Message: This is another view of the kind of work I showed you on the last postcard.

And to think this could be done with nothing but the sand as found along the beach.

According to the city directory, James Taylor worked in Atlantic City as a sand sculptor in 1899 and as a hotel waiter in 1904. His work as a sand sculptor in Atlantic City and the beaches of California was well recorded on postcards and newspaper articles.

The motif of “Cast Up by the Sea” would have resonated with the public during this era. Shipwrecks were not uncommon at the time, and similar subjects were described in art and literature. The scene is possibly based on works like this 1873 wood engraving by Winslow Homer, also titled “Cast Up by the Sea.”

Postcard of 1873 wood engraving, “Cast Up by the Sea,” Winslow Homer.

By 1908, sculptor James Taylor had left Atlantic City for the West Coast, where he worked the beaches of California for a few years, and he complimented the moldable nature of the sand when compared to that of the Atlantic coast. The woman clutching a babe to her breast was usually the centerpiece of his work, and her dress, full of folds and undulations, took Taylor about two hours to complete. He knew how to work the crowd, waiting until a decent number of onlookers had gathered before he began a piece. He never mourned the fleeting nature of his chosen art form and their loss to the incoming tide, saying, “The material is still there, and I can do the work again.”

James Taylor working in front of the Steel Pier, circa 1906.

Postcard titled, “Afternoon Tea.” James Taylor 1906.

Note the two sticks at the waterline, which may have helped Taylor keep track of the incoming tide.

1909 postcard, James Taylor, Cliff House, San Francisco.

James J. Taylor was born in 1860. He died at Seaside Hospital, Long Beach, in 1918. He had been found in a shack on Alamitos Bay, ill and destitute. Taylor had often admonished his audience, “Don’t forget the worker,” as a way of asking for donations or tips and recognition for the class of “workers” and himself. His work and name remain today on thousands of old postcards and photographs. Time, like the incoming tide, washes the sand clean again.

But wait, what about Philip McCord?

After the apparent sand sculpture of “Cast Up By the Sea” in 1897, Philip McCord seemed to disappear from the scene…

However, a few sources mention a shadowy “sand artist” who wandered the Midwest for 20 years or more, drifting like a hobo but occasionally stopping to sculpt the figures of “Cast Up by the Sea” in sand or riverbank mud.

An article in the April 16, 1915 issue of the Moberly Weekly Monitor, Moberly, Missouri, titled “Sculptor Astonishes Citizens with Life-Size Model of Mother and Babe,” reported that a man had arrived in town who gave his name only as “Sand Artist” as he worked in a pile of wet sand and fashioned the classic subject. The newspaper reported that he worked at the end of North Williams Street and molded a pile of sand into a work he called “Washed Up By the Sea.” The artist said he worked in ashes or mud when no sand was available.

Was this visitor to Moberly Philip McCord? In a book by Don Eggspuehler, Teachings from Pop, AuthorHouse Press, 2014, the author relates a story about a mysterious sculptor who wandered Kansas and Iowa, occasionally carving the figures of a mother and babe into riverbank sand. The artist told onlookers that the figures represented his wife and child who drowned in the Pueblo, Colorado floods of 1922; he went on to say that he had studied art at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. Eggspuehler’s account mixes the stories of Philip McCord and that of James Taylor, but he goes on to speculate about Philip McCord “making a meager living touring the country coast-to-coast carving the same scene over and over.”

A current online story by the Argus Newspaper Museum in Table Rock, Nebraska, reports a recent finding of a 1921 photograph and newspaper article in the museum’s archives titled “Cast Up by the Sea.”(5) Museum tour guide Sharla Sitzman reported finding the photograph below and an April 22, 1921, Argus Newspaper article which gave the artist’s name as J. B. McCord. He said he was from Philadelphia and had worked with some of the greatest artists in the country. McCord worked the sandy soil beside a creek using only his hands and a butcher knife. Beside him on the ground lay a sign that said, “Throw a penny to the artist.” It was estimated that he collected perhaps $15... and moved on...

Photograph of creek-side sculpture by Mr. McCord

Argus, Table Rock, Nebraska, 1921